- Opportuna Newsletter

- Posts

- Klarna's IPO Moment - From Transactions to Super App (Part 2 of 3)

Klarna's IPO Moment - From Transactions to Super App (Part 2 of 3)

How Klarna Makes Money—and What It’s Betting On Next

This is the second post in a three-part series on Klarna’s IPO and its evolving business model.

In Part 1, we explored Klarna’s rapid ascent—from dorm-room idea to fintech juggernaut—and the pressures that forced a pivot from hyper-growth to profitability.

This post dives into Klarna’s revenue model, its underlying unit economics, and its bold ambition to become a financial super app.

In Part 3, we’ll examine Klarna’s competition and analyse the key medium and long-term priorities for the business.

How Klarna Earns from Merchants, Advertising, and Consumers

Klarna makes money through two main channels: transaction-based fees and interest income. Both are anchored to Gross Merchandise Volume (GMV) - the total value of completed purchases across its platform over a given period - and Klarna’s ability to extract economic value per dollar spent.

This is measured in payments parlance as the take rate, expressed in basis points of GMV. Klarna’s take rate rose from 230 basis points in 2022 to 267 basis points in 2024.

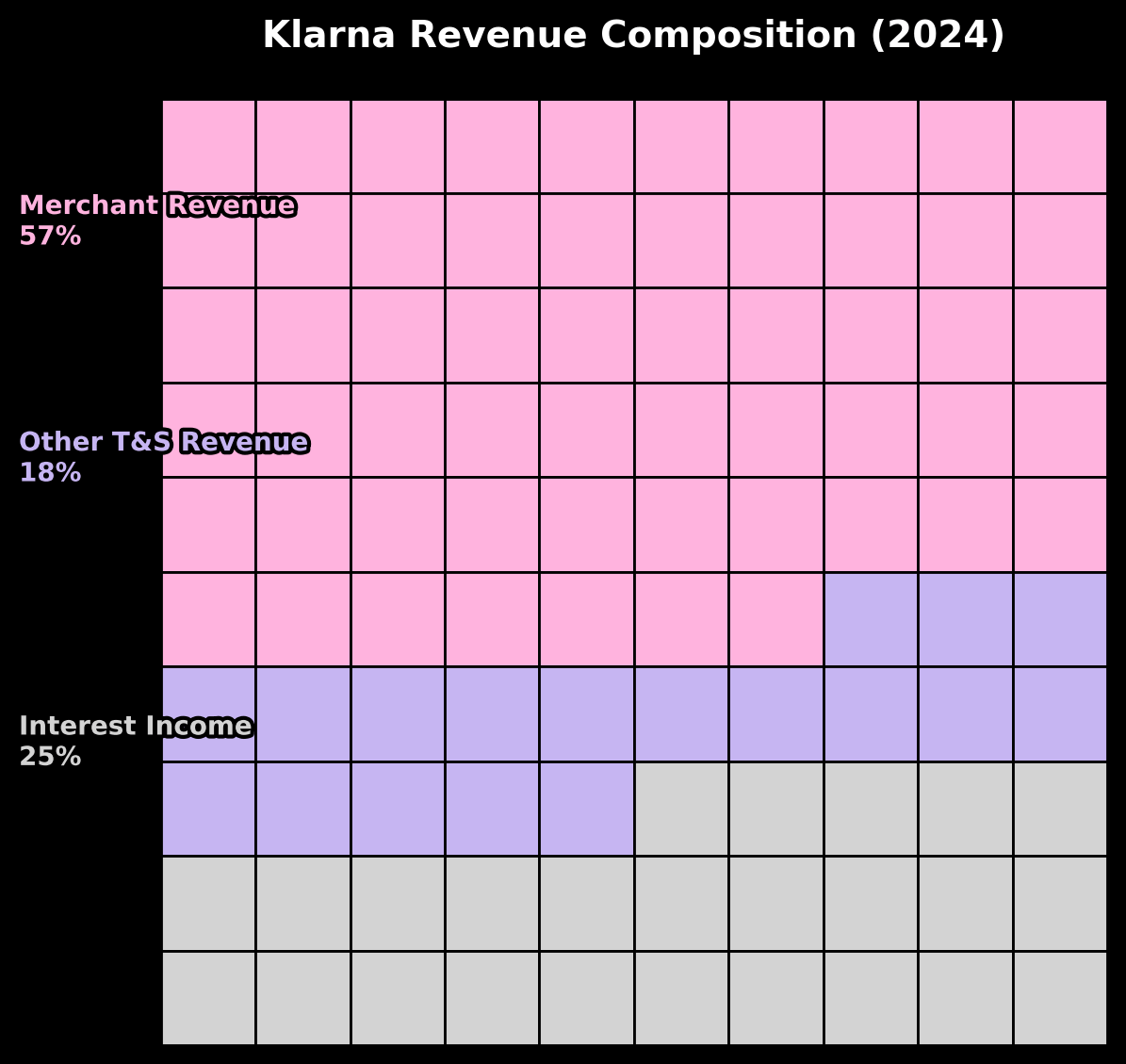

Transaction and Service Revenue makes up 75% of Klarna’s top line and includes:

Merchant Revenue (MR): The primary driver of revenue. Merchants pay Klarna a fee when customers transact on the platform. Pricing combines fixed and value-based components and varies by region.

Advertising Revenue: Klarna earns fees from merchants who advertise through its app and website, including sponsored search results, affiliate marketing, and branded placements.

Consumer Service Revenue: Fees charged directly to consumers, primarily late fees and charges for administrative features such as one-time card issuance.

Interest Income arises when consumers choose interest-bearing financing (branded Fair Financing) or delay payments using features like “snooze.” Since 2021, Klarna has only charged interest on loans longer than three months - its Pay Later and Pay in Full offerings remain interest-free. Klarna also earns interest from debt securities in its investment portfolio.

In 2024, 57% of Klarna’s revenue came from Merchant Revenue, which grew 19% year-over-year. That growth was driven 70% by GMV expansion and 30% by take rate improvement.

Source: Klarna F-1

Gross Margin, Klarna-Style: Breaking Down Transaction Economics

To assess unit economics, Klarna focuses on transaction-level costs:

1. Processing and Servicing Fees: Costs related to payment settlement, authentication, and risk scoring. These declined from 63bps to 57bps of GMV between 2022 and 2024.

2. Credit Losses: Realized and anticipated losses from Klarna’s consumer lending activities.

3. Funding Costs: Net interest expense to finance consumer loans, primarily interest paid on customer deposits and other borrowings.

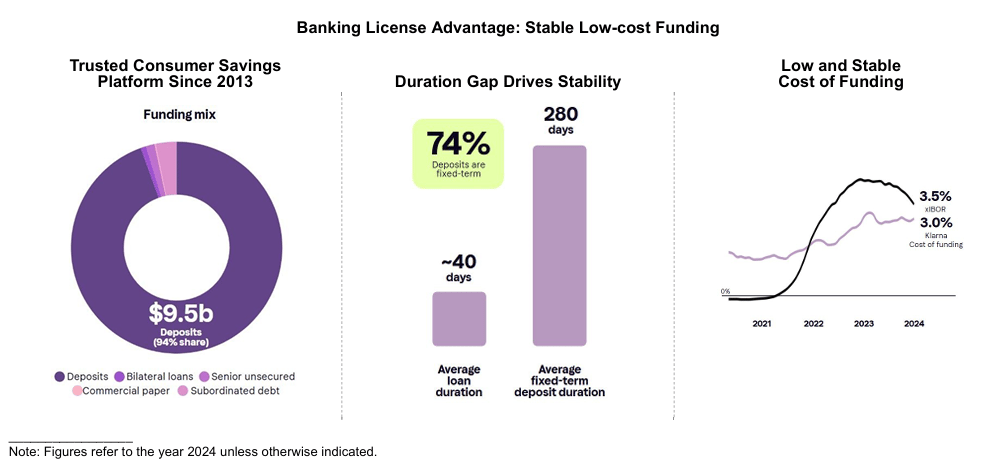

Though Klarna brands itself as a tech company, its economics increasingly resemble those of a digital bank. In 2024, 94% of its funding came from customer deposits - an attractive source of stable, low-cost capital. In times of stress, this could be a strategic advantage over rivals reliant on wholesale or venture funding, which can evaporate when markets tighten.

Source: Klarna F-1

The difference between revenue and these direct costs is what Klarna calls transaction margin dollars. It is a proxy for gross margin - a measure of profitability before fixed operating costs. It reflects the earnings power of its core business: facilitating payments while managing credit risk. In our first blog post of the series, we highlighted transaction margins deteriorated as a result of rising funding costs (interest rates) and international expansion into lower-margin markets.

Affirm discloses a similar non-GAAP metric, Revenue Less Transaction Costs (RLTC), benchmarked against GMV rather than revenue. It deducts loan purchase losses, credit loss provisions, funding costs, and processing expenses from total revenue. While definitions vary slightly, RLTC and transaction margin both serve as useful indicators of unit economics. In part 3 of the series, we provide more insights into Klarna’s economics relative to others.

Klarna’s Super App Ambitions: A Commerce Network in the Making

To diversify, Klarna has invested heavily in becoming more than a BNPL provider. Today, these initiatives remain, from a revenue standpoint, peripheral; Klarna is still fundamentally a payments company with a lending arm, trying to become a super-app. In the future, however, Klarna has a few shots on finding compelling ways to attract and retain both users and merchants:

Klarna Card: A physical and virtual card enabling consumers to use Klarna’s payment options - Pay Later, Pay in Full, and potentially Klarna Balance - both online and in-store. This expands Klarna’s footprint into omnichannel commerce and encourages everyday use.

Klarna App (Digital Wallet): A central interface for shopping, managing payments, tracking orders, accessing deals and cashback, and integrating Klarna Balance. It’s a key lever to deepen engagement and drive ecosystem growth.

Klarna Balance (Deposit Account): An in-app account where users can store funds, receive refunds, earn cashback, and initiate payments. By embedding financial functionality, Klarna positions itself as a more integral part of the consumer’s financial life.

Klarna’s pivot from a pure BNPL player to a full-spectrum “super app” is a bid to become the default interface for online shopping and payments. The Klarna Card, Klarna App, and Klarna Balance are not just new products; they’re strategic attempts to deepen engagement, boost frequency, and capture more of the commerce value chain.

Klarna is building a closed-loop commerce network that combines real-time underwriting, checkout distribution, and proprietary consumer data. With 2.5 billion SKU-level data points and 93 million users, Klarna can offer merchants performance marketing in a commerce-centric environment.

The app’s shopping, tracking, and cashback tools are designed to move Klarna upstream in the customer journey, capturing intent before checkout. This matters: whoever owns the consumer’s decision moment can monetize it through payment, ads, or both. Klarna’s AI assistant is an ambitious bet to power this interface, with personal shopping and financial insights becoming the next frontier.

If Klarna succeeds, it will look less like Affirm or PayPal—and more like a fintech-native version of Amazon, Shopify, or even TikTok for commerce.

Conclusion

Klarna’s core business remains firmly rooted in payments and credit. But the company is positioning itself to own more of the consumer journey — from intent to checkout to post-purchase management. Its foray into cards, wallets, and deposit accounts isn’t about competing with banks — it’s about increasing relevance, retention, and revenue per user.

Klarna’s ambition is clear: build a closed-loop commerce ecosystem where it controls both data and distribution. If it pulls this off, Klarna could evolve from a BNPL provider into a next-generation fintech platform—one with the scope of Shopify, the engagement of TikTok, and the monetization engine of PayPal.

The next post in this series will explore how Klarna’s economics compare to peers, and the key medium and long-term priorities for the business